The new ruler of the kingdom of Sicily, Charles I of Anjou, inherited the old goals of the Norman Altaville and German Hohenstauf dynasties. At the center of his foreign policy was the conquest of the East and the capture of Constantinople. This policy was constantly encouraged and nourished by the Church of Rome, which counted on organizing, through the Angevins, a new crusade against Byzantium and thus realizing the violent union of the churches. It was in the presence of Pope Clement IV that the agreement between Charles I of Anjou and the dethroned Latin emperor of Constantinople, Baldwin II, was signed in Viterbo in May 1267, according to which the latter transferred his rights in the East to the Angevin king . The agreement in question defined as the first stage of the Angevin enterprise the occupation of a headland on the Albanian coast,Charles I of Anjou tried to assert his hereditary rights over Manfred’s Albanian possessions, turning Manfred’s collaborators in Albania into his vassals. In this framework, in 1267, Charles I appointed as his viceroy in Albania Gaco Kinard, a relative of the murdered viceroy of Manfred, Philip. But neither the castle of Corfu, nor that of Vlora, Butrint and Sopot, nor Captain Vrana and the citizens of Durrës heard of passing under Angevin sovereignty. On the contrary, King Karl’s relations with the opposite coast remained honorable until 1271. At that time, he himself expressed in a letter that the Albanians “hate his name” (in odium nostri nominis).

However, the Angevins did not undertake any armed campaigns. Charles I tried to attract the Albanian leaders through promises and in 1271 he seems to have established a dialogue with the aristocracy of Arbri as well as with the civic community of Durrës. During that year, two Albanian Catholic priests, John of Durres and Nicholas of Arbri, as confidants of King Charles and his great ally, Pope Gregory X, made several trips between Naples and Durres, conveying the king’s messages to the Albanian leaders . At the beginning of February 1272, a delegation of the nobility of Arbri and the civic community of Durrës arrived at the Angevin court in Naples. At the end of the negotiations with Charles of Anjou, the union of the “Kingdom of Arbri” (Regnum Albaniae) with the Kingdom of Sicily was announced under the sovereignty of King Charles (Carolus I,

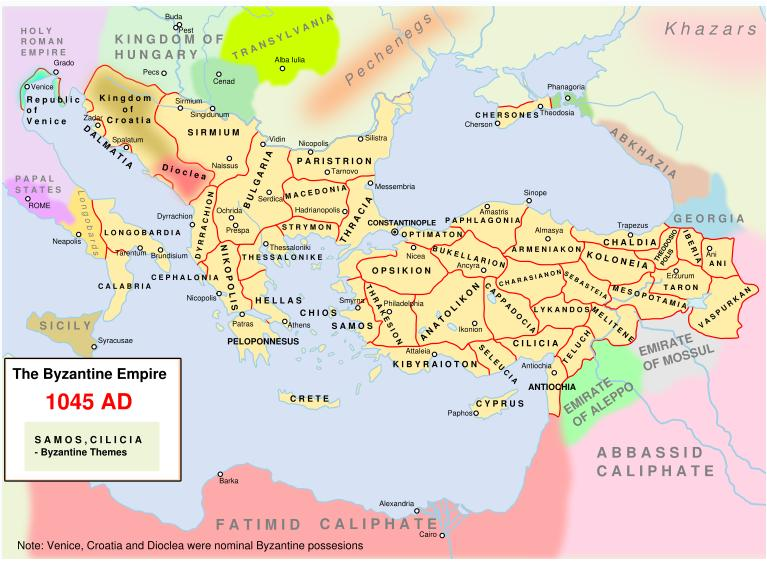

The turn of the Albanian nobles in the relations with the Angevin king happened for a number of external and internal reasons. At that time, the Byzantines and the Serbs had increased the pressure on the Albanian territories that were still outside their control. The Serbs had already approached the Dibra area, while the Byzantine Empire had re-established its rule in a good part of interior Albania. The capture of Berat immediately after the Byzantine victory at Pelagoni (Manastir) in 1259 gave Byzantium a very important strategic base to further extend its area of control to the coastline.

To the difficulties of the Albanian aristocracy in relations with these foreign powers, the divisions and conflicts between the Albanian nobles themselves were added. At this time, even the former Principality of Arbri had lost the splendor it had at the time of Prince Dhimitër. Instead of a feudal family, several families exercised their influence and power in the territory of Arbri, often in conflict with each other, such as the Skurra, Vrana, Blinishti, Topia, Arianiti, etc. families. In this way, the recognition of a foreign sovereign was also seen as a means of calming rivalries between them. Finally, the fact that in Albania, especially in the area of Durres and Arbri, there was already a philo-Angevin group, represented mainly by the Catholic clergy of Durres and Arbri, that under the rule of Manfred, the fierce enemy of the Papacy, had suffered persecution from the fiercest. Consequently, he was inclined to cooperate with the new ruler of Sicily, Charles of Anjou, who, unlike Manfred, was the beniamin and the right wing of the Roman Catholic Church.

Despite such motives that spoke in favor of the Angevins, the compromise of 1272 between the Angevins and the Albanian aristocracy became possible only after Charles I of Anjou gave the Albanian leaders the required guarantees. In two diplomas issued by his chancellery on February 20 and 21, 1272, he promised them his protection (protectionem suam) and the recognition of all privileges, norms and previous “good” docks. Their text clearly shows that the recognition of the Angevin sovereignty by the Albanian leaders was not an unconditional “surrender”, but an agreement reached, as King Charles himself said, “without any violence or coercion” (absque aliqua violentia seu cohactione). The Angevins basically satisfied the two basic demands of the Albanians: the demand for an Angevin commitment in the honorable relations of the Albanians with other powers, mainly Byzantium and Serbia.

Despite the tempting promises of the Angevins, not immediately and not all the Albanian nobles were attracted to them.

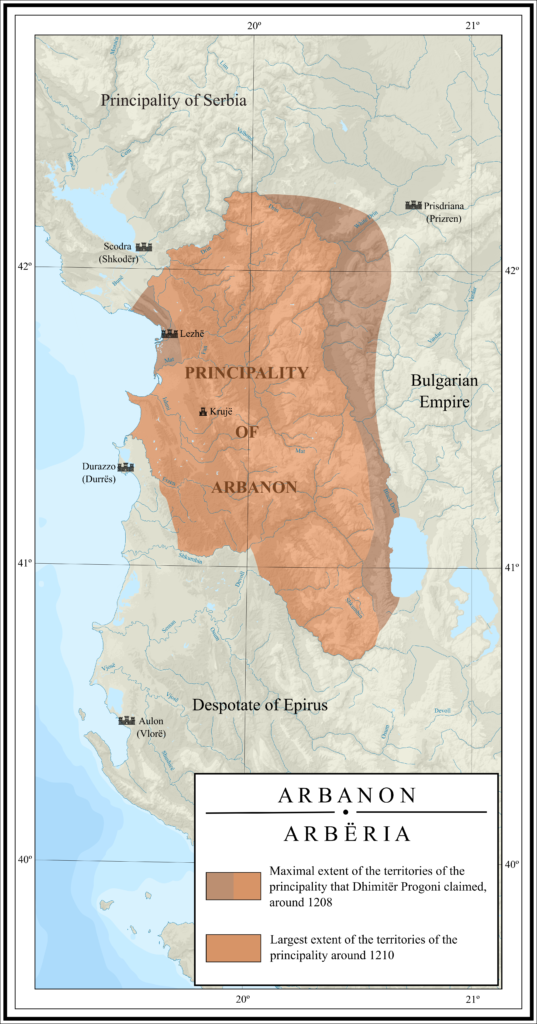

The long time it took Charles I of Anjou to realize his plan was the best proof that there was reluctance among the Albanian aristocracy regarding a pro-Anjou orientation. In fact, the Angevins defined from the beginning the space between Durres and Vlora, or more precisely between Mati and Seman-Devolli, as the area of their vital interests in Albania. The Angevins saw the lands outside them first of all as a function of the relations with the allied Balkan states, in the first place with the kingdom of Serbia. This political line of the Angevins broke them from the beginning with an important wing of the Albanian aristocracy. The alliance with the Serbian Kingdom was always an advantage for Karl Anzhu, and he refused to protect the Albanian nobles, such as Gropajt e Dibra, whose lands were under the threat of Serbian occupation.

ut the relations of the Angevins did not take long to break even with their nobles-vassals of the “Kingdom of Arbri”. The promises related to the recognition of autonomy and old privileges, which Charles I had given to the Albanian leaders in the beginning, were shown to be demagoguery. Albanian nobles were forced to perform the “feudal oath and homage” (ligii homagii iuramentum). A strong military administration was established here, where the Albanian aristocracy was not represented in any of its instances. All the officials, from the “captain and viceroy of the Kingdom of Arberia”, to the marshal, castle guards, intendants and lower positions, were of Franco-Italian nationality. Albanians were excluded from any effective role in this “Kingdom of Arberia”. The Albanian nobles, who recognize Karl I Anzhu as their leader and who were included in the “Kingdom of Arberia”, were organized by the Angevins in a kind of “regency council”. Charles I set the limit of their rights and duties, when he advised them that “they should obey the vice-captain general of the Kingdom of Arbri and help him with all their strength and in every work, either with advice or with means necessary”. The Angevin documents clearly indicate where the help of the Albanian chiefs for the Angevin lord consisted. In the first place they had to accompany the Angevin troops in military campaigns. This service of theirs corresponded to the essence of the Angevin regime and the “Kingdom of the Arbri”, which the Angevins designed and built as a core of an entire Balkan empire. The Albanians had to fight, thus, for a purpose that was not theirs and that they did not feel. This disappointed their initial hopes.

But the new Angevin regime did not only have negative consequences on the political level. The Angevins imposed a strict regime of exploitation on their possessions. Large land funds were seized from local owners, primarily opponents of the Angevin regime, and distributed to the benefit of the crown, the functionaries of the Angevin feudal lords and the Catholic churches, assemblies and monasteries founded in large numbers by foreign clergy, who came together with the Angevins who represented a social support and a means of their ideological diversion. The Albanian peasantry, who worked on these lands, was subjected to an intense and unknown exploitation until then. Large revenues entered the royal coffers of the Angevin officials from the taxes and duties that they often arbitrarily imposed on the local population.

The establishment of the Angevin regime also had negative reflexes in the life of the cities. Their autonomy was narrowed, the municipal governing bodies ceased to function and were replaced by the Angevin administration. The economic interests of the merchant-artisan and small classes were severely damaged by the policy of the state monopoly on the production and sale of the main products, as well as by the various obligations that the Angevin officials imposed at the expense of the citizen population. The many revenues that came from the production and trade of salt went to the benefit of maintaining the troops and the Angevin administration in Albania.

In this way, the Anjou regime aroused disappointment and discontent among the most diverse layers of Albanian society in the first months. The Albanian aristocracy, inside and outside the framework of the “Kingdom of the Arbri”, became the mouthpiece of this discontent, which saw that the Angevins violated its political aspirations without hesitation. In order to force the Albanian leaders to remain loyal to him and not rise up, Charles I began to take their children as hostages, whom he took and kept in the castles of Southern Italy, where they were treated as if they were prisoners. so much so that in many cases they tried to escape.

The clashes between the Albanians and the Angevins, from the beginning of the latter’s settlement in Albania, favored the game of the Byzantines. Starting from the summer of 1272, the Byzantine emperor Michael VIII Palaeologus was in contact with the Albanian nobles and tried to make them his own and throw them against the Angevins. His effort was based on the promises and guarantees he presented to the Albanians, and there is no doubt that at this point he did not lag behind, he even surpassed his rival, Charles I of Anjou, as long as he managed to do for himself from the very beginning (“deceive “, according to the expression of Charles I) enough of them.

In the summer of 1274, the Angevin documents themselves speak of an operative alliance between the Byzantines and the Albanian nobles. In August of that year the allies had achieved a first victory over the Angevins, causing them many casualties and taking many more prisoners. In November, the Angevin commanders in Albania reported to the Angevin king Karl that “the Arbëresh and Byzantines had surrounded Durrës”. Later information confirmed that the fighting was already concentrated in the vicinity of the Byzantine fortresses. The outbreak of open conflict with the Albanians caused the battle front to move rapidly to the vicinity of the Angevin castles on the coast.

The attractive force of this new orientation of the Albanian aristocracy against the Angevins became those nobles who had maintained a reserved attitude towards the Angevins and who were not included in the “Kingdom of Arbri”. Such were Pal Gropa and Gjin Muzaka, lords respectively of the area of Dibra and that of Berat. Over time, these nobles were joined by others, from those who were known as vassals of King Karl. In a rather significant way, Charles I of Anjou begins to call nobles such as the Blinishte, Skurraj, Jonim, etc., who until then had been “his faithful” (fideles suos) by the name “my traitors” (proditores nostros). This new attitude had fatal consequences for the Angevin rule. The Albanian possessions of Karl Anzhu or, as he preferred to call them, the “Kingdom of Arbri”, which was nothing more than a number of possessions of Albanian nobles,

The new course taken by the relations of the Albanians with the Angevins, and the Albanian-Byzantine alliance that followed, overturned the great plans of Charles I of Anjou, who had hoped to lead his armies as far as Constantinople. Moreover, the plans of the Angevin king were also compromised by the rapprochement of the Byzantine emperor, Michael VIII Paleologus, with the Pope. The agreement these two reached at the Council of Lyons, in 1274, to bring about the union of the churches, isolated Charles of Anjou by depriving him of the unconditional support of the Papacy. Instead of continuing his march to the East, Charles was forced to sign a truce with Michael VIII Paleologus (1276). Meanwhile, the “Byzantines” had turned Berat into the center where, together with the Albanian nobles, operations were organized against the Angevin castles. They entrusted the command of this castle to a local nobleman, Sebasti Stano, who performed the function of the headman (governor) of the city. At that time, the Byzantines had also managed to capture Spinarica, the coastal locality between Vlora and Durrës. In this way, the southern possessions of the Angevins were separated from Durrës through this Byzantine wedge from Berat to the coast. Interconnections between the Angevin possessions and between them of the Kingdom of Sicily were carried out only by sea. But even maritime communication had become dangerous, because a Byzantine fleet based in Spinarica and Butrint attacked Angevin ships. the southern possessions of the Angevins were separated from Durrës through this Byzantine wedge from Berat to the coast. Interconnections between the Angevin possessions and between them of the Kingdom of Sicily were carried out only by sea. But even maritime communication had become dangerous, because a Byzantine fleet based in Spinarica and Butrint attacked Angevin ships. The southern possessions of the Angevins were separated from Durrës through this Byzantine wedge from Berat to the coast. Interconnections between the Angevin possessions and between them of the Kingdom of Sicily were carried out only by sea. But even maritime communication had become dangerous, because a Byzantine fleet based in Spinarica and Butrint attacked Angevin ships.

Seeing the disastrous state of his troops in Albania, King Charles I of Anjou thought of organizing a new campaign, during which he would subdue the rebellious Albanian leaders and take the castles occupied in the meantime by the Byzantine emperor Michael VIII Palaeologus. In this context, special importance was given to the Berat castle, against which the main Angevin attack was concentrated. Taking Berat would free the coastal bases of the Angevins (Vlora, Durrës) from Byzantine pressure and would create the conditions for the advance of Charles of Anjou’s armies inland. It is for these reasons that Charles I wrote to the commander of the Angevin army in Albania that “he could not express in words the importance he gave to the conquest of the castle of Berat” (ad captionem castri Bellgradi, que ultra quam dici valeat cordi nostro residet).

On the eve of the invasion, Charles I of Anjou confirmed the alliances with Serbia and the Despotate of Epirus. Despot Niqifori I of Epirus was declared a vassal of the Angevin king and handed over to him the castles of Butrint, Sopot and Porto-Palermo. But first of all, Charles I made a new effort to fix the relations with the Albanians and to separate them from the Byzantines. In this framework, Charles I freed a number of insurgent Albanian leaders from Italian prisons, among them Gjin Muzak, who was kept “bound with strong iron shackles” in the Brindiz castle prison together with Dhimitër Zogu, Kasnec and Guljelm Blinishti. Charles I of Anjou received repeated requests from the Albanian nobles to release Muzaka. Apparently, Gjin Muzaka enjoyed a special position and authority and through him the Angevin king tried to influence the Albanian leaders. In August 1280, he ordered the release of the slave Muzaka, “after he had given his wife and children as hostages and after he had sworn that he would no longer join the enemies of King Karl and would no longer speak and act against him.” . In the conditions of the preparation of the Angevin lesson on Berat, the neutralization of the Muzakai, lords of the country, took on a special meaning.

However, the efforts of the Angevins for diversion in the ranks of the Albanian aristocracy did not yield results. On the eve of the decisive battle for Berat, the news that came to Charles I from his commanders in Albania informed him that “the Arbris had risen again and were attacking the Angevin troops”. The determined anti-Angevin attitude of the majority of the Albanian nobles decisively determined the progress of the Angevin school. While Hugo de Sylt’s army, reinforced by contingents from Durrës, Vlora and Butrinti, had closed the siege of Berat, the Albanians attacked the Angevin castles on the coast, forcing the Angevin commander to distract his forces and start reinforcements in the direction of those castles.

The Angevin siege of Berat lasted several months. In December 1280 the Angevins were finally able to occupy the outer quarters of the city (suburbia). But in the final battle, which took place in the spring of the following year on the banks of the Osum, the defenders of the castle inflicted a heavy defeat on the French cavalry, capturing even the commander of the Angevin army.

After the defeat of Berat, the Angevins quickly retreated to the coastal edge, where they were able to protect for some time the important castles of Durrës, Vlora and Kanina. In 1282, Charles I designed a new campaign against Byzantium, but that same year, the great anti-Angevin uprising of the “Sicilian Evenings” broke out in Sicily, in which the Byzantine emperor, Michael VIII Palaeologus, and the king of Aragon also had a hand. After that began a 20-year period of wars between the Aragonese and the Angevins for the possession of Sicily. Under such conditions, the new expedition against Byzantium remained unrealized. The castles that the Angevins held for several years on the Albanian coast remained as isolated islands under constant siege by the Albanians and the Byzantines. In 1285, the Angevins also abandoned Durrës, Vlora and Kanina. The fortresses of Butrint, Sopot and Porto-Palermo, which they were able to hold in the south, in the territories of the Despotate of Epirus, were support points without any special strategic importance. In this way, after about 15 years of efforts to gain and maintain their positions in Albania, the Angevins were forced to withdraw and give way to the Byzantine Empire, which thus restored its authority in a good part of the Albanian lands .